History of Homelessness

Homelessness has surged and receded throughout the nation’s history, with spikes during the colonial period, pre-industrial era, post-Civil War years, Great Depression, and today.

While there are many drivers of modern-day homelessness, it is largely the result of failed policies; severely underfunded programs that have led to affordable housing shortages; wages that do not keep up with rising rents and housing costs; inadequate safety nets; inequitable access to quality health care (including mental health care), education, and economic opportunity; and mass incarceration. In effect, more than half of Americans live paycheck to paycheck and one crisis away from homelessness.

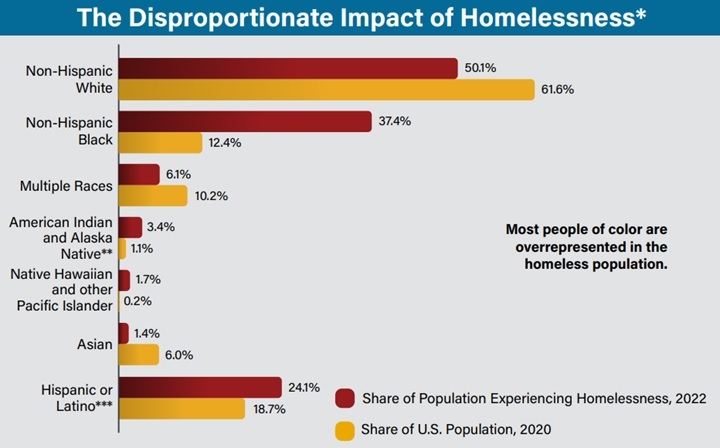

At the root of these systemic failures is historical and ongoing racism. From slavery and the Indian Removal Act to redlining and mass incarceration, people of color and other historically marginalized groups (such as LGBTQI+ youth) have been denied rights and excluded from opportunities in ways that continue to have negative impacts today.

State of Homelessness

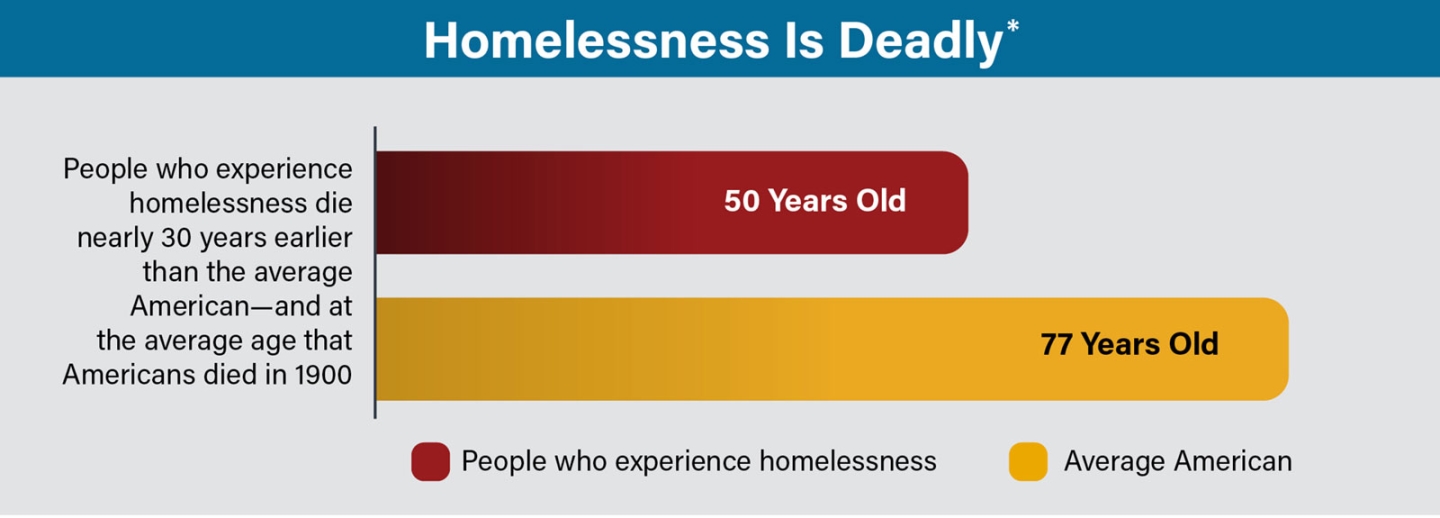

Homelessness in the United States is an urgent public health issue and humanitarian crisis. It impacts cities, suburbs, and rural towns in every state. Housing is a social determinant of health, meaning lack of it has a negative impact on overall health and life expectancy. Tens of thousands of people die every year due to the dangerous conditions of living without housing—conditions that have worsened due to climate change’s rise in extreme weather. People who experience homelessness die nearly 30 years earlier than the average American—and often from easily treatable illnesses.

Given the pervasiveness of homelessness, most Americans—often unknowingly—have friends, family, coworkers, or neighbors who are experiencing homelessness today or who have experienced homelessness at some point in their lives.

While homelessness impacts people of all ages, races, ethnicities, gender identities, and sexual orientations, it disproportionately impacts some groups and populations. Compared to the portion of the U.S. population they make up, people of color, for instance, are overrepresented in the population experiencing homelessness.

People with preexisting health issues are also more likely to experience homelessness—particularly unsheltered—and they are up to seven times more likely to lack health insurance. While rates of homelessness for people with severe mental health or substance use issues are high, the majority of people experiencing homelessness have neither a severe mental health nor substance use issue. Furthermore, the large majority of Americans with mental health and substance use issues do not experience homelessness.

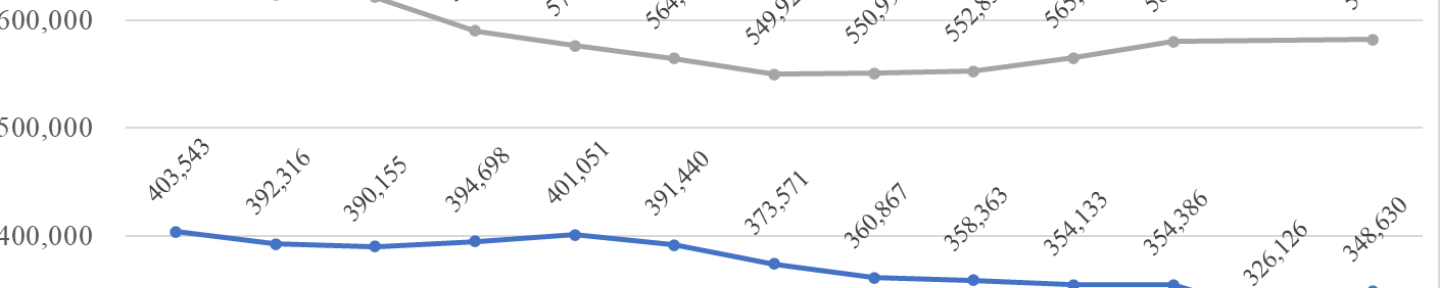

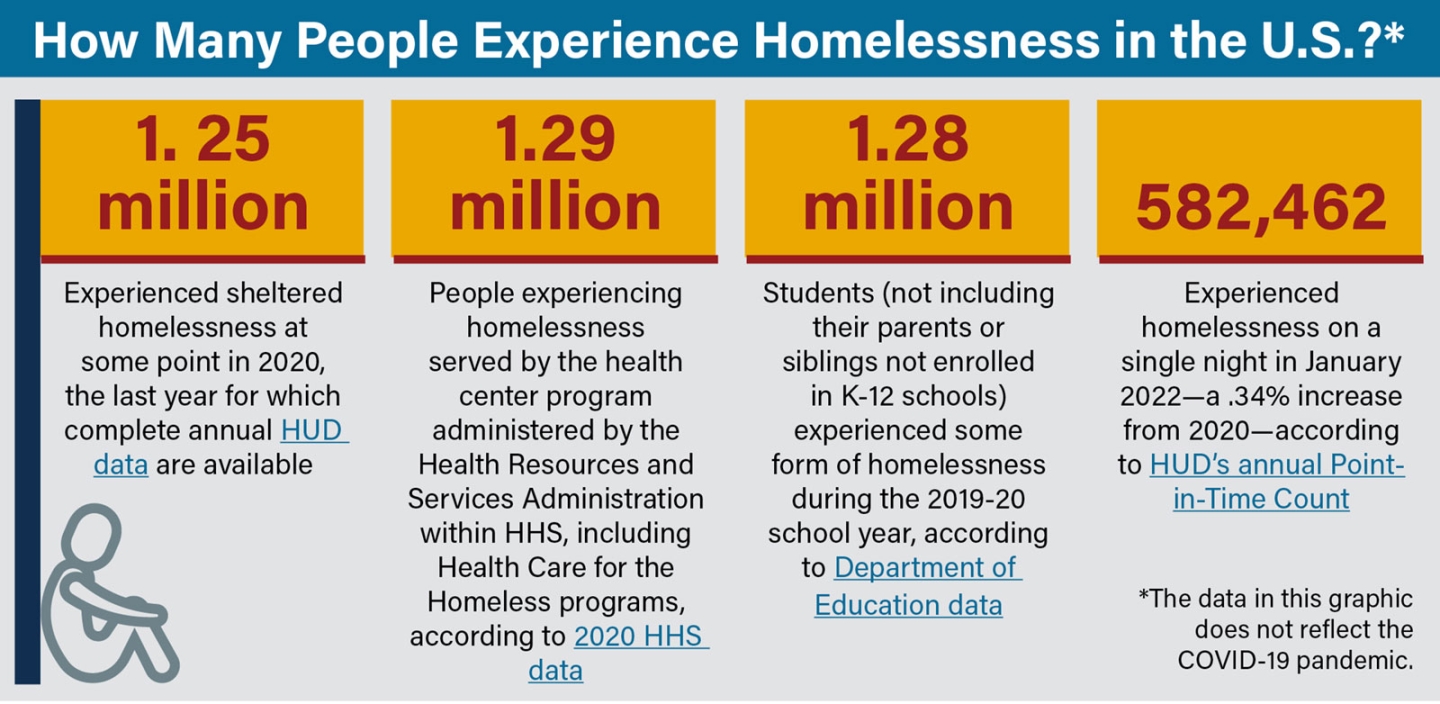

Homelessness Data

There are two main sources of federal homelessness data: the Annual Homeless Assessment Report, published by the Department of Housing and Urban Development; and the Annual Student Homelessness in America Report, published by the Department of Education’s technical assistance operator, the National Center for Homeless Education.

Several other agencies—including the departments of Agriculture and Defense; the Census Bureau; the Office of Head Start; and the Health Resources and Services Administration—collect data on homelessness that USICH publishes in reports, which can be found here.

Homelessness Fact vs. Fiction

There are many myths about the causes of and solutions to homelessness, particularly the “Housing First” approach that has been proven by decades of research to be effective and cost-effective. Below are some of the most common myths—and the reality surrounding them:

Myth: People experiencing homelessness just need to get a job.

Fact: While employment helps people stay housed, it does not guarantee housing. As many as 40%-60% of people experiencing homelessness have a job, but housing is unaffordable because wages have not kept up with rising rents. There is no county or state where a full-time minimum-wage worker can afford a modest apartment. At minimum wage, people have to work 86 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom. Even when people can afford a home, one is not always available. In 1970, the United States had a surplus of 300,000 affordable homes. Today, only 37 affordable homes are available for every 100 extremely low-income renters. As a result, 70% of the lowest-wage households spend more than half their income on rent, placing them at high risk of homelessness when unexpected expenses (such as car repairs and medical bills) arise.

Myth: People experiencing homelessness choose to live outside in tents or cars.

Fact: Homelessness usually happens because of economic reasons (such as job loss), and many people have nowhere else to go but outside. Many shelters are full or limited to people who are sober, straight, free of disability or criminal history, and/or willing to separate from their children, partners, or pets. These discriminatory policies leave parents, couples, pet owners, LGBTQI+ members, and people with addictions, disabilities, or criminal records on the streets, where they live in constant fear of hunger, violence, storms, and infectious disease. “Out of sight, out of mind” laws that make it illegal to sit or sleep in public outdoor spaces only exacerbate the revolving door between homelessness and incarceration, and they do not solve homelessness. Housing and supports solve homelessness—not handcuffs.

Myth: People experiencing homelessness are dangerous and violent.

Fact: Not having a home does not make someone a criminal, just like having a home does not make someone innocent of any and all crimes. According to data, people experiencing homelessness are far more likely to be victims of violent crime than to commit violent crime. But because of the infrequency of violent crimes committed by people experiencing homelessness, they tend to be considered “newsworthy” and attract more media attention.

Myth: Most people experiencing homelessness have a substance use and/or mental health disorder.

Fact: While rates of homelessness for people with severe mental health or substance use disorders are high, the majority of people with no home also have no mental health or substance use disorder. Furthermore, the large majority of Americans with mental health or substance use disorders do not experience homelessness, demonstrating that mental health and substance use disorders do not cause homelessness.

Myth: Homelessness is not preventable.

Fact: Homelessness is a policy choice, and the COVID-19 pandemic proved the power of prevention. During the pandemic, governments instituted eviction moratoriums, deployed emergency rental assistance, expanded unemployment assistance and the Child Tax Credit, and issued cash directly to millions of lower-income Americans. In effect, poverty dropped by 45%, millions of evictions were prevented, and homelessness remained steady during a time when a surge in homelessness would have been expected.

Myth: Housing First only helps people get housing but does not address the issues that led them to homelessness—and could again.

Fact: The Housing First approach recognizes that housing is the immediate solution to homelessness—but not the only solution. Housing First offers support (such as substance use treatment, legal aid, or job training) at the same time as housing and continues to offer support long after people are housed to prevent them from losing their home again. One element that sets Housing First apart from some other approaches is that it does not force people to accept support. Forced mental health or substance use treatment, for instance, is proven to be largely ineffective and to have unintended, harmful, even deadly consequences.

Myth: Housing First is expensive and ineffective.

Fact: Decades of research prove how effective and cost-effective Housing First can be. Studies show that 9 out of 10 people remain housed a year after receiving Housing First assistance, and that housing can be three times cheaper than criminalization. According to a recent study, Housing First pays for itself within 1.5 years and can reduce homelessness and government reliance—all while getting people back to work.